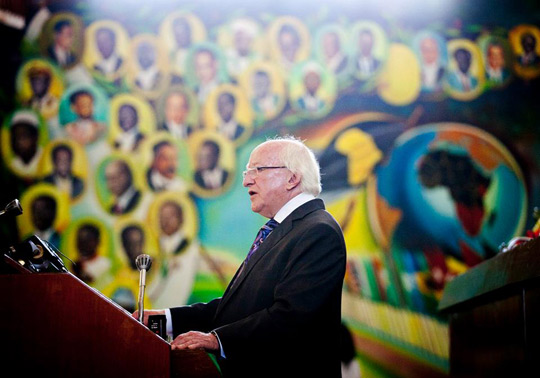

President’s keynote address delivered at Africa Hall, in the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa

“Independence and inter-dependence in Africa”

Address by Michael D. Higgins, President of Ireland

To the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Wednesday, 5th November, 2014

Dr. Lopes,

Their Excellencies, the Honourable Representatives of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia,

Excellencies,

Distinguished Guests,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Is mór an áthas a bheith anseo libh i Halla na hAfraice, ceannáras stairiúil Choimisiún Eacnamaíoch don Aifric na Náisiúin Aontaithe, in Addis Ababa na hAetóipe, ar seo, mo dhara chuairt ar an Aifric mar Uachtarán na hÉireann.

It is a great pleasure to be here with you all in Africa Hall, the historic headquarters of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa in Addis Ababa, on what is my second visit to Africa as President of Ireland.

May I thank you, Dr. Lopes, for your very kind words of welcome – you paid us the courtesy of a visit to Ireland last week and I am deeply grateful for the warm hospitality you are extending today to me, to our Minister of State for Development and Trade Promotion, Mr Seán Sherlock T.D, and to the entire Irish delegation.

My visit to the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia is the first leg of an African visit which will also include the Republic of Malawi and the Republic of South Africa.

The purpose of these visits is to reinforce Ireland’s bilateral relations with each of the three countries; but also to listen, and encounter, the new departures under way or being considered by Africans for the future of their people, and it is an opportunity for me as President of Ireland to manifest Ireland’s desire to expand and deepen our co-operation with Africa generally, building on our longstanding ties of diplomatic exchanges, missionary activity, development co-operation, and friendship.

Indeed relationships with African countries have long formed an important strand of Ireland’s foreign policy and the significance of those relationships is only increasing, due to the intrinsic global nature of the most pressing challenges of our times, such as climate change, food security, poverty reduction, the fate of refugees and asylum seekers, the upsurge in religious intolerance, and, of course, the urgent threats posed by the current Ebola crisis.

It is my profound conviction that any authentic engagement with the global interdependence that binds our peoples together, the theme of my address this morning, cannot rest solely on any self-interested, or pragmatic, stance, – for example any notion that we, Europeans, must help fix problems beyond our borders, lest the poor, the hungry, the countryless, the vengeful of the world, will ultimately break through these borders.

Any deep-seated recognition of our interdependence across continents must be more firmly grounded, I contend, in a shared ethical consciousness – a vision of socio-economic development that places human flourishing at its heart. My hope in this new century, therefore, is that we will endeavour, together, to build a cooperative, caring and non-exploitative civilisation, based on the firm foundations of recognising each people’s own institutions and traditions, experiences and memories, including those that will inevitable recall old wounds and failures and opportunities lost, but will also be based on a recognition of the solidarity that binds us together as human beings, and an acknowledgement of the responsibility we share for our fragile planet and the dignity of all those who dwell on it.

It is fitting that I should start my visit to Africa here in Ethiopia, the cradle of humanity. On Sunday, my first appointment in Addis Ababa was at the National Museum, to see ‘Australopithecus Afarensis’ – also called ‘dinknesh’, ‘the wondrous one’, in her Ethiopian homeland, and better known to many of us as ‘Lucy.’ This 1.1 metre tall skeleton of a female estimated to have lived 3.2 million years ago symbolises the debunking of the pseudo-science of 19th century European racial anthropologists and white supremacists.

The discovery made by Donald Johanson in 1974 changed forever scientific understanding of human origins, and constituted the principal milestone on the road to the epoch-making discovery that the first woman was not a white Eve, but an “irretrievably black” Eve, to borrow a term employed by Reginald Dumas in his book on Haiti.

We Irish people were never proud proponents of racial supremacy theories. Over the course of our history, rather, we were more often than not on the receiving end of such, as the victims of imperial notions of racial difference and superiority – from the 17th century onwards, when a stereotypical package of attributes was directed at our people, with the purpose of justifying the superiority of the coloniser over the colonised. This perhaps suggests an explanation why the Irish can be prone to identify, in sympathy and imagination, with those people who strive for their freedom.

Indeed Ireland’s national history and your own national histories, however distinct they may be, are ones that chime – and it is why, in your recollections, we hear echoes of our own past.

We Irish experienced too, in addition to the scourges of colonisation, that of hunger – “the terror of the hungry grass”, as Irish poet Donagh MacDonagh described it. It is no surprise, then, that our memories of those terrible events of the 19th century Irish famine, An Gorta Mór or the Great Hunger in our own language (for we found it difficult even to put a name on it); and of the dark years and massive emigration that followed, inform Ireland’s enduring commitment to development cooperation with its African partners.

In the twentieth century, the Irish people also had to struggle for independence, and we endured the subsequent harrowing destabilisation of civil war. Thus the memory of our emancipatory struggle continues, today, to inform our outlook on the world, our interpretation of the narratives and projects of others. The vindication of the dignity and freedom of individuals and the freedom of the peoples of other nations; the importance of justice and compassion – these are there in the bedrock of our values as a nation. And we know, too, how difficult it is to secure or vindicate the values that might have motivated the struggle for independence in a post-independence experience.

One of the figures of the struggle for Irish freedom was Roger Casement, who, as a diplomat in the British Foreign Office, dedicated much effort to investigating the brutal and dehumanising effects of colonial rule in the Belgian Congo at the turn of the 20th century, that is, at a time when few questioned the righteousness of European colonial empires.

In Casement’s work we can find the seeds of the contemporary language of universal human rights, and a defence of the fundamental equality and dignity of all human beings, regardless of colour, gender, race or creed. As to human labour, his writings also contain a strong call to adhere to the development of humane working and living conditions for the people.

Casement’s rejection of colonialism, his revulsion at its practices – brought to an extreme in a continent like Africa – led him to embrace the path of the Irish national revolution, and ultimately to his death. At his trial for treason in front of a British court, he said:

“Self-government is our right, a thing born in us at birth; a thing no more to be doled out to us or withheld from us by another people than the right to life itself.”

I think of Roger Casement, and many men and women like him, whenever I read the opening lines of the solemn Charter adopted at the opening summit of the Organisation of African Unity (the OAU), which, half a century later, invoked “the inalienable right of all people to control their own destiny”.

Indeed it is impossible to stand in this impressive building – Africa Hall –thinking of the early days of African unity; without recalling in one’s mind the 32 delegations arriving here for that first summit, in May 1963. Africa was not entirely free then. Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Angola had yet to achieve independence, and it would not be until 1994 that the first universal suffrage elections would be held in South Africa.

Back in 1963, the leaders of newly independent countries saw the need for multilateral institutions to promote understanding and solidarity between the peoples of Africa. They understood the importance of co-operation between states to respond to their people’s aspirations for democracy, peace, security and social, economic and cultural development.

There was “no clear consensus”, however, for as Emperor Haile Selassie put it,

“On the ‘how’ and the ‘what’ of this union. Is it to be, in form, federal, confederal or unitary? Is the sovereignty of individual states to be reduced, and if so, by how much and in what areas?”

Fifty years later, this debate as to the form, extent and pace of regional integration remains unsettled. Conflicts of leadership between the OAU’s member states, armed conflicts between neighbouring countries, disregard, even at times, contempt for democracy and the rights of citizens in too many countries have shattered the promises of regional integration.

Looking back on those first two decades since 1963, Julius Kambarage Nyerere thus reflected with a saddened heart these words:

“We spoke and acted as if, given the opportunity for self-government, we would quickly create utopias. Instead injustice, even tyranny, is rampant.”

Yet, none of us should be defeated by aims or projects not realised. Five decades is a short time, but a moment, in the history of this great continent, and African leaders have achieved much in those 50 years. Decolonisation and the fight against apartheid South Africa, two of the OAU’s main objectives, have been completed. In 2002, the African Union succeeded the OAU – and the new generation of leaders who work together within this African Union have inherited and are endowed with the crucial transformational task of shepherding the path from independence to a new form of inter-dependence.

Today we in Ireland exercise our shared sovereignty in the pursuit of a real union of European states, a Union that puts the aim of social cohesion on an equal footing with that of competitiveness as an economic region; a European Union of citizens committed to solidarity between each other and in solidarity with the ethical aspirations of a truly global community.

It might seem superficially odd that a country like Ireland, that spent centuries struggling for independence, would chose to pool its sovereignty in a broader union within a matter of decades. Yet I believe that this decision to pool our hard-earned sovereignty with other European Union member states is a choice which, ultimately, enhanced our sovereignty – a move that defined a new role for us in Europe and the wider world, provided us with new economic opportunities within an expanded, regional single market, opened up new horizons for our citizens, and – nearer home – brought a new maturity to our relations with the United Kingdom, our former colonial power.

It has been a remarkable turnaround, which happened within the space of a generation. My father fought for Irish independence, and in April of this year, I became the first Head of that independent State to accept an invitation to pay a State Visit to our close neighbour the United Kingdom. Today Ireland and Britain are equal partners within the European Union – friends who trade together, who are able to revisit their common past with openness and mutual respect, and who work, for example, together to support the reconciliation process in Northern Ireland. We recognise, too, that the settlement achieved in Northern Ireland between Dublin, Belfast and London brought with it a new set of possibilities for building on our independence project.

I believe that such a constructive vision of their interdependence can, today, guide the regional cooperation between African countries as they face into the challenges brought about by the new century. It can also serve as a basis for concerted action between African states and their partners in the wider world, towards achieving social and economic progress for all of our global citizens.

The scale of the global challenges we face together requires not only a recovery of the impulses of the past which drew us forward towards a new world; it requires also new models, new scholarship, that will generate new relationships with each other and with our fragile planet.

Over the past couple of decades, the world has undergone a reorganisation that gave supremacy to dangerous notions as to the efficiency and sustainability of the self-regulated market; and that led over that time to a hostility towards and a shrinking of state action. This shift was underpinned by very narrow scholarship and models of economics which, however, became hegemonic. The global financial meltdown of 2008 has revealed an enormous institutional and regulatory void in coordinating and governing markets so that they might operate for the common good. From these failed paradigms we must break free.

It is important that we reaffirm strongly, today, the significance of multilateral institutions such as the UN, and of regional organisations such as the European Union and the African Union, in safeguarding the needs and expectations, not just of their member states, but above all also of their citizens. If this is to happen, it is also important that our young people have the opportunity for a pluralist education, one that enables critical scholarship and can serve as a basis for a diverse range of policy options.

Dear Friends,

The last fifty years might have passed like the blink of an eye for Lucy, but for the peoples of Africa, they have been of fundamental importance. Africa’s growth performance has improved dramatically since the years 2000. This has been underpinned by a number of factors, such as the commitment to peaceful democratic elections in ever more countries; strengthening domestic demand associated with rising incomes and urbanisation; increased public spending, particularly on infrastructure; intensification of trade and investment ties with emerging economies; and abundant harvests in several countries. Although, we must never forget that the origin of cities in history lie in the generation of rural surplus in their hinterlands.

Today Africa is at a critical juncture of its development. The discourse has moved on from war and disadvantage to debates about vindicating human rights and the nature of citizenship in culturally diverse settings. As Léopold Sédar Senghor put it, “Africa is not an idea, it is a knot of realities” – realities that can be shaped in order to deliver human progress and sustainable development. African leaders working together within the African Union, civil servants in organisations such as this Economic Commission for Africa, civil society activists across the continents are wise in taking note of the lessons that can be drawn down from hegemonic models of economics that have failed, both here and in our countries; and they are wise in endeavouring to produce their own forms of thinking – including alternative models of development that are socially, culturally and ethically grounded.

The evolving global order of this 21st century thus presents Africans with many opportunities, and also with challenges, but ones which – if met with by effective and concerted policies at the regional and global level – can lead to positive socio-economic transformation.

The first of these challenges remains, in my view, that of food security. Indeed the continent’s population is expected to double, from around 1 billion to over 2 million people by 2050, and the most fundamental task of finding appropriate ways to feed such an expanding population is rendered even more critical, in this century, by the additional, and largely uncharted, problems posed by climate change.

This issue of food security concerns all of our countries. Crucially, in facing this issue, we must consider the role of those interests who are involved in the global infrastructure of commodity trading, governed as it is by powerful global financial markets. And the question of knowing if speculation on food commodities is an acceptable practice is, I believe, one whose resolution cannot be led by the whims of the market. It must, rather, be the object, of multilateral regulation based on a shared ethical consciousness of the special status of farming and food products, upon which hinges the survival of so many.

My friend Professor Howard Stein, who contributed to the recent 2014 UNECA annual economic report on industrial policy, convincingly argued, in a 2012 paper he presented to a conference at Trinity College Dublin, against speculation on food commodities. As he put it:

“Commodity markets are being driven not by fundamentals of producers and end users but by other factors. Among other things, commodities are seen as good hedge when the value of the dollar falls which lowers the value of global commodities in non-dollar terms … In 2011, for example, it is estimated that 61% of the wheat futures market was held by speculators compared to only 12% in the mid-90s prior to deregulation.”

While African commodity exporting economies have benefited greatly from recent sustained increases in the price of their primary commodities, I believe that it is timely and important to ask if such ‘rents’ can be relied upon as an enduring engine of growth and development. How can African countries, and their partners beyond Africa, tackle the power of financial agents, who have become such key players in driving speculation and fluctuations in commodity markets? Whose interests do these markets really benefit, and whose needs do they cater for? Such questions will have to be addressed sooner rather than later. If we are to experience a globalisation that is ethical, they cannot be met with silence or inactivity on the part of multilateral institutions who are seriously concerned about the survival of the poorest.

As one explores the relations between agriculture, food and security – the triptych chosen by the African Union as its theme for 2014 – the question of access to land also emerges as a pivotal issue, not least because of its vital relevance to the survival of the poorest in Africa’s rural areas. This is an issue I have discussed in a previous speech at Trinity College Dublin’s Africa Day earlier this year, and it is one to which I will return in the address I will give at the Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources, in Malawi, next week. But I believe that it deserves a mention, here this morning, as we reflect upon the challenges facing contemporary Africa.

I would like to avail of this occasion to salute the United Nations’ decision to declare 2014 the International Year of Family Farming. The need to relocate family farming at the centre of African national agendas, including trade policies, is all the more pressing in light of the scale of the current phenomenon of land grabbing, whereby large swathes of the countryside that are considered “idle” are being sold or transferred through long-term leases to usually foreign investors.

There is no question that the demographic challenge, in particular the need to provide for growing demand from the continent’s mushrooming cities, calls for a pro-active policy response. Yet, it is a concern that must be expressed, that those massive transfers of land, organised in the name of the ‘modernisation’ of African agriculture and ‘more efficient food production’, might be pursued at the expense of the food security of the local farming population?

It is my belief that – if supported by appropriate policies at local, regional and global level – new models can proliferate, beyond, or as an alternative to, the expansion of large plantations.

As we reflect on the future of African farming, it is perhaps appropriate to critically consider, for example, Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto’s model of land parcellisation, which has mesmerised so many policy makers over the last few decades. Indeed de Soto’s approach appears particularly problematic from the point of view of rural common property resources, which have fluid boundaries, and which are required to be continuously adapted to fit people’s social needs, and are rarely exclusive to one person, but involve, instead, multiple layers of relative rights. Uncritical acceptance of such a model is capable of creating the most devastating consequences on rural families.

What strikes me most is the intellectual blind spot in de Soto’s conception: his formal property has as its main characteristic that of individual private ownership, and its primary function is the generation of capital, through its use as potential collateral for loans from private institutions. Other functions, such as, for example, the significance of land for the social continuity of groups, for ideas of kinship and ascendancy, for intergenerational solidarity, are ignored.

We must, urgently, seek alternatives to the reductive, narrow imagination of mainstream models of development such as de Soto’s. Land tenure has been the subject of too many disastrous experiments in engineering, both physical and social. It is now time, I believe, for us to turn to Africans to imagine and craft inclusive agricultural development policies for Africans, that are grounded in a recognition of the need to feed an expanding regional population, while also taking care of a fragile and exhaustible natural environment, and taking on board the heritage of indigenous wisdom and the wealth of practices and conceptions that connect people to their land.

A profusion of ideas and projects are already underway; many alternative models are being developed across Africa, which accommodate the complex nature of rights in many rural contexts, such as, for example, the concept of “adverse possession”, as it is being elaborated in South Africa.

Interestingly, many of these projects are underpinned by a vision of rights as being communal as well as individual. In his own time, Julius Nyerere had a keen sense of the tension between individual and collective conceptions of rights, and the need to find the right balance between the two. These are his words, from a speech he gave in 1960:

“Having come into contact with a civilization which has over-emphasized the freedom of the individual, we are in fact faced with one of the big problems of Africa in the modern world. Our problem is just this: how to get the benefits of European society – benefits that have been brought about by an organisation based upon the individual – and yet retain African’s own structure of society in which the individual is a member of a kind of fellowship.”

Community solidarity, of course, is present in a myriad of forms in contemporary Africa. Ireland is proud to support, for example, Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Nets Programme, which encourages members of local communities to give of their time and labour for a set number of days in support of public works. Whether we call it ‘ubuntu’, ‘umuganda’, ‘harambee’, ‘debbo’ or, more prosaically, the Productive Safety Nets Programme, there are so many ancient and modern expressions of co-operation and interdependence across this continent that point towards a different way of living, and a different way of viewing the world around us.

In Ireland, in Europe and globally, we have paid the price of an excess of individualisation, a confusion between individual freedom and the pursuit of self-interest, a reduction of the concept of freedom to a narrow freedom of the unregulated and unreliable market. Against the current trends in increasing commodification of life, I believe that it is vital that we recover a sense of the public world, so essential to our lives together.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Today this public world is also threatened by the upsurge of intolerance, here in Africa, and beyond. This is not a new threat. In his speech to the Union of African Unity, in 1963, Léopold Sédar Senghor said:

“We must begin by rejecting all fanaticism, whether racial, religious or linguistic. Then, and then only, can we define our aim lucidly.”

The scale of the contemporary challenge is reflected in the presence on African soil of so many soldiers from the rest of the world who are engaged in seeking to prevent hotbeds of conflicts from emerging or escalating, conflicts often fuelled by the misuse of ressources.

Many of these conflicts thrive on poverty and a new geography of inequalities, which sees the path of prosperous African centres – many of them connected to the maritime trade routes of our contemporary globalisation – diverge from that of interior regions, which descend into being enclaves of misery and revolt, enclaves plagued by unemployment and lack of opportunities.

Here as in Europe, we know how unemployment, and in particular endemic youth unemployment, feeds rancour and frustration. Ireland has one of the youngest populations in Europe, but of course this continent’s population is incomparably younger. Africa’s formidable demographic dynamism is available to express itself in the fields of citizenship, education, economic innovation and social transformation.

The key challenge, therefore, is one that we also currently face in Europe: how to create jobs, in particular for the young? This ties, of course, into another, more fundamental question: what is real growth? To what extent are indicators such as GDP, of which we know that they have fared particularly high in Africa over the last couple of decades, an appropriate measure of social development?

In that 1963 speech of his, to which I referred, Senghor expressed his views on this question in the following terms:

“The aim we must assign, which we do assign, to our action can, obviously, only be the very aim which other nations and continents have set themselves: development through economic growth. I say development. By that I mean bringing each and every African to full worth. It is about mankind.”

To be faithful to this vision of one of the founding fathers of African unity, our aim must be, not just to seek higher growth rates, but to ground more firmly our strategy for growth in an ethical reflection on the social goods which we want this growth to deliver. We must endeavour to define the kind of growth that is best able to bring about the basic goods necessary for our citizens to lead a good, decent life. Here in Africa, as in Ireland, our shared project must be not only about the right to survive, but about the right to flourish.

And in that regard, I was very interested to read UNECA’s 2013 economic report – Making the Most of Africa’s Commodities: Industrialising for Growth, Jobs and Economic Transformation – which offers a very stimulating reflection on global value chains and the new opportunities with which they present Africans.

The report convincingly argues that the way for Africa to achieve inclusive economic growth is to develop effective industrial policies and commodity-based industrialisation. Indeed the vast shifts in global production and trade patterns mean that new possibilities have emerged for connecting to global economic actors and for adding value to locally produced commodities in a manner that fosters economic diversification, job creation and socio-economic development.

Private companies and the big investors that control global value chains cannot be relied on to promote local linkages and interactions beyond their own interests. African governments therefore need, the report suggests, to make strategic interventions to empower indigenous firms to insert themselves in regional and global value chains. This report also asserts the benefits of regional cooperation and the need to develop regional markets, which may initially be less demanding, and thus allow local firms to build the production capabilities required to move up into more competitive global chains.

To some extent, one could say that the ability of the Irish government to strategically insert the Irish economy in emerging global value chains, from the mid-1990s onwards, coupled with access to the Single European Market, are factors which underpinned Ireland’s healthy economic development, before our economy was engulfed in a credit-led, speculative property bubble.

We can well imagine where Africa will be when it will manage to effectively harness cooperation between its regional economic communities to boost the level of inter-African trade and to add value locally to its own commodities, for the primary benefit of its citizens.

All this, of course, can happen only if African governments, individually, and in concert within the African Union and other fora for regional cooperation, deliver on the aspirations for peace and security of their citizens.

It is also crucial to recall that peace and stability will not be achieved, on this continent and globally, lest we tackle head-on the terrible predicament of millions of men, women and children who were forced to leave behind their homes, communities and means of survival to seek refuge elsewhere. This is an issue that concerns us all, and not just the countries first affected and their immediate neighbours.

Ethiopia has a history of receiving people displaced by cross-border movements, due to droughts, conflicts, political events and civil wars in its neighbouring countries, including Eritrea, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan. I want to pay tribute to the government of Ethiopia for maintaining an open-door-policy and having continuously allowed humanitarian access and protection to those seeking refuge on its territory. Today the country is home to a population of over 600,000 refugees, who are mainly accommodated in camps distributed across the Ethiopian territory, including in Dollo Ado, Shire, Gambella and Assosa.

May I also commend the extremely important work carried out by the Ethiopian refugee agency, the Administration for Refugee and Returnee Affairs (ARRA) – who is the UNHCR’s main governmental partner in Ethiopia – and to the patient mediation efforts led by the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD).

These agencies, and the NGO workers involved on the ground, are performing incredible tasks in very difficult circumstances. For example, I know that the plight of Eritrean refugees, in particular unaccompanied minors and children who are separated from their families and who tend to move on to third countries, presents a major challenge for those who endeavour to provide them with appropriate protection.

Yesterday, I travelled to Gambella, where I met many amazing people – first and foremost the refugees themselves, who are bearing the consequences of the ongoing conflict in South Sudan with stoicism, dignity and courage. This conflict which has driven them across the border is most dispiriting: after all that has been invested in bringing the world’s newest state into being, the people who expected so much from their own independence, have been quite frankly let down.

In Ireland, as in many African countries, we know what it means to move from a war of independence to a civil war. Our own war of independence was followed immediately by a bitter civil war which sapped much of our energy and talents, for years, even generations. My own country’s history and, sadly, the war in South Sudan today, remind us that achieving independence is far from being the end of the journey – the requirements of democracy, the need to accommodate the rights of minorities, are challenges that are ever more demanding, and we must all do our best to support a sustainable peace process in South Sudan.

Faced with the enormous scale of the refugee problem globally, Europe cannot be content with its current management of migration flows. We should never forget that European countries developed themselves, in previous centuries, by sending millions of their own people to other continents. And what would have happened to the Irish people, had they been denied the possibility to emigrate to the New World in order to escape starvation at home in the mid-19th century?

The current situation, which sees migration to rich countries close to blocked, leaving so many with no other option than to cross the Mediterranean, our Mare Nostrum turned mass graveyard, in highly perilous circumstances – this situation is a moral scandal. There can be no resolution to this defining issue of our times without a sharing of responsibilities instead of what Pope Francis described as the current “globalisation of indifference.”

Finally, the most immediate challenge to the stability of this continent is, of course, the Ebola crisis, which is devastating parts of West Africa. I am, like everybody here, horrified by the tragic loss of life – and, on behalf of the Irish people, I want to pay tribute to the courageous health workers, doctors and nurses, who have responded and who will response to the battle to contain the virus.

But we must do more. We must do more, for example, to support the efforts of the “African Union Support to Ebola Outbreak in West Africa” (ASEOWA) mission. I know, Dr. Lopes, that you have just returned from the region, having visited the worst-affected areas with the Chairperson of the African Union, Dr. Dlamini-Zuma. The focus you are applying to finding solutions to this terrible crisis is appreciated far and wide, beyond the region and beyond the continent.

We should all be ready to work with you to find the answers the afflicted countries need. It is essential that every possible effort is put in place to get a grip with the virus before it threatens the prosperity that Africa has begun to enjoy over the last few decades.

We should recognise very clearly that Ebola is a disease that thrives on poverty. Indeed the conditions that facilitate the tragic spread of the disease are underpinned by poor health services, migration from rural areas that are unable to sustain the livelihoods of an expanding population, which in turn feeds anarchic urban development and overcrowded housing conditions in many quarters of Africa’s booming cities.

South Africans sometimes talk of what they call “ubuntu”, a concept which describes our inter-connectedness with other human beings, our community, our environment, and the wider world. This is not a moment to succumb to fear and an instinct for self-preservation which would put at risk the great hopes, the economic and social progress that has been underway for over a decade across the African continent. This is a moment when we need to embrace a local, regional and global “ubuntu.” A moment to show solidarity, between Africans, and with Africans.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

The various challenges I have mentioned all have economic, social, political, cultural and moral ramifications. Tackling them requires a collective effort, not just from Africans but from the rest of the world too. Tackling them will require also a freedom to imagine new models of social, economic and cultural development for our shared future.

By this time next year the world’s leaders will have adopted a new set of global development goals. The United Nations have appointed Ireland and Kenya to co-facilitate the international negotiations on the new global development agenda. This leadership role is both a great honour and a huge challenge for Ireland. I can assure you that we will do our best to foster an agenda that is both faithful to the greatest hopes of the founding fathers of African independence and unity, and responsive to the requirements of our acknowledged interdependence in this new century.

Mar focail chun scoir, which means in our ancient language “to finish”, the characters staring at us from Afewerk Tekle’s stained glass tryptich – “The Total Liberation of Africa” – that overlook the staircase behind you remind us of the spirit which animated the founding fathers, fifty years ago. Ramatoulaye, the leading character in Mariama Bâ’s So Long a Letter is another powerful voice who recalls for us the excitement of those years of liberation. Let me quote her words:

“It was the privilege of our generation to be the link between two periods in our history, one of domination, the other of independence. We remained young and efficient, for we were the messengers of a new design.”

Now it is the privilege of another generation to be the link between two periods in our shared history. I like to think of them all, past and present, as pilgrims, with each pilgrimage representing a different chapter in the story of a continent on the move.

As this new generation takes on the mantle of transformation and change, my hope would be that they retain the utopian, emancipatory charge of Afewerk Tekle’s work of art, while – perhaps – discarding the word “total” from its title, which is too redolent of the darkest passions of the 20th century. Indeed in our interconnected and complicated world, cooperation, the pooling of resources, a recognition of our interdependence, offer more secure and fruitful grounds for our mutual relations than any absolutist version of sovereignty.

In the decades to come, then, Africans are invited to find their singular voice, a voice of freedom but also a voice of fidelity to their rich history and traditions.

In the very long term, in the multi-secular temporal horizon which is that of Lucy, we are all but migrants in time and space – transient travellers who must do our best to pass on to the next generations a hospitable ground on which they can flourish.

Go raibh míle maith agaibh go léir.