Wed, 23 Sep 2020 16:29:45 BST

Frederick Douglass in Ireland, 1845-46 - Ambassador's Blog

News

23 September 2020

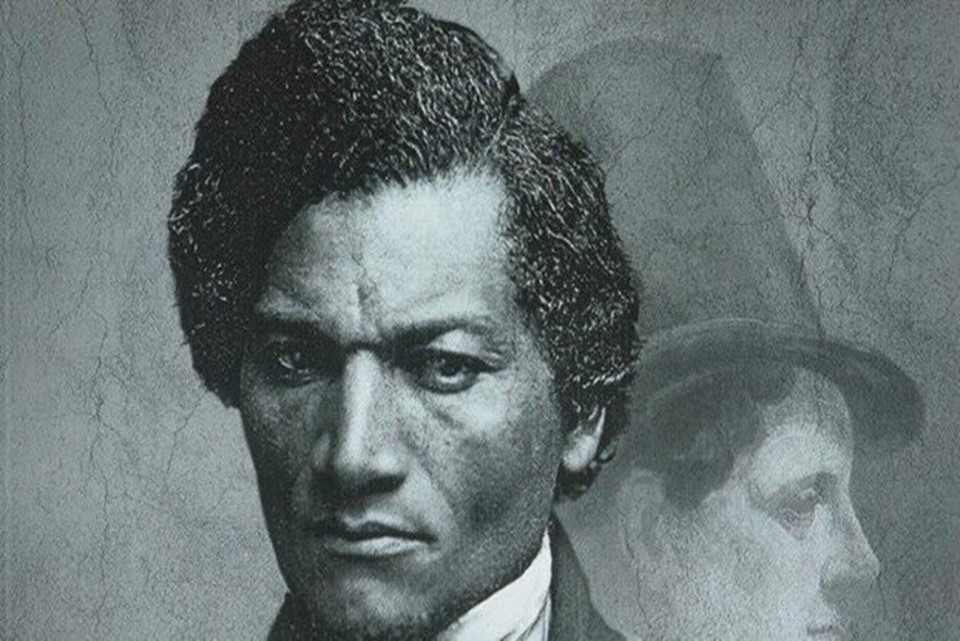

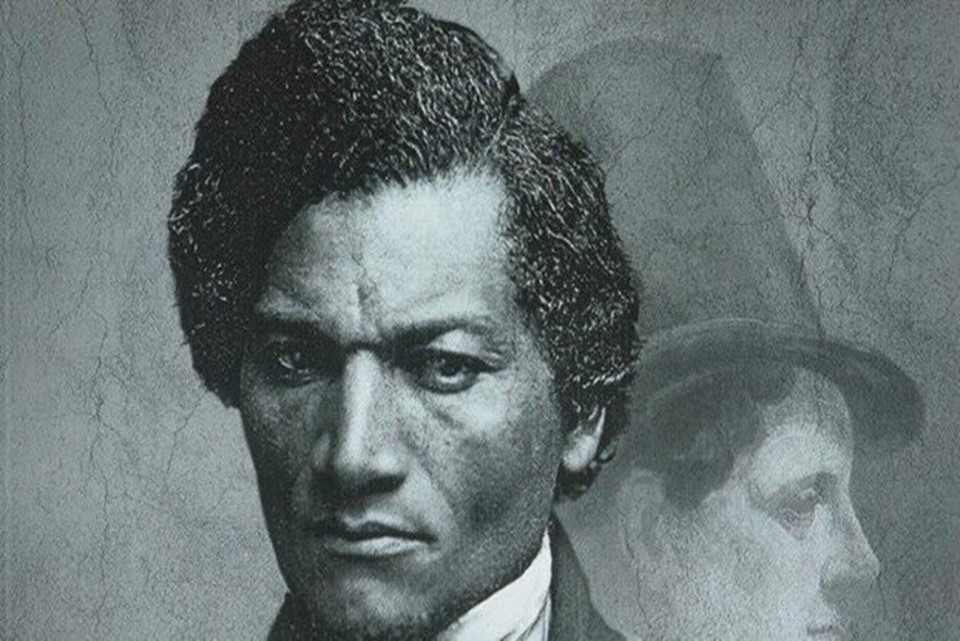

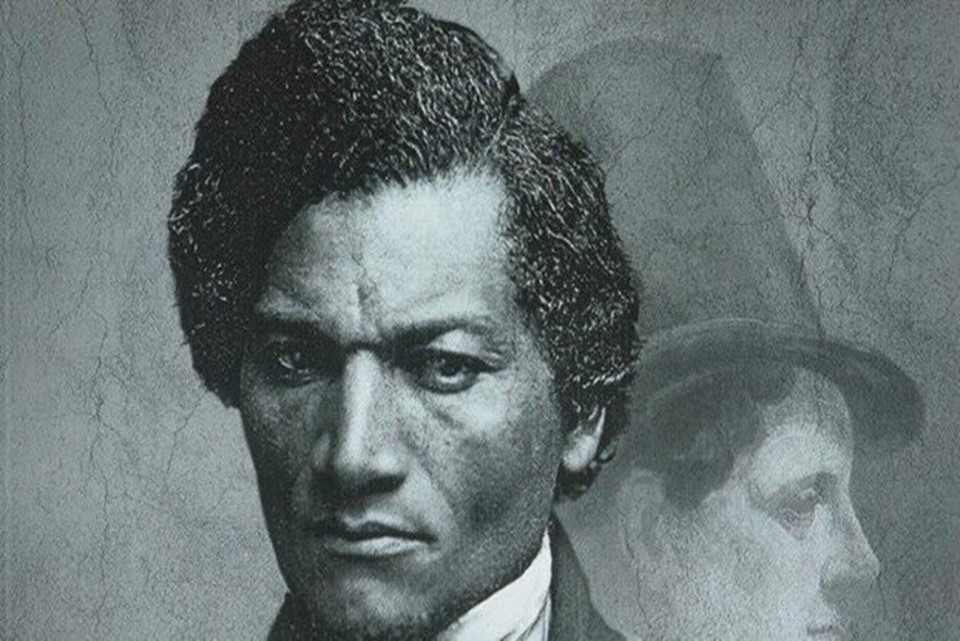

Frederick Douglass & Daniel O'Connell

“I can truly say, I have spent some of the happiest moments of my life since landing in this country. I seem to have undergone a transformation. I live a new life.” – Frederick Douglass, letter to William Lloyd Garrison, 1 January 1846 the day he left Ireland

“I despise any government which, while it boasts of liberty, is guilty of slavery, the greatest crime that can be committed by humanity against humanity.” – Daniel O’Connell speaking in 1845, the year of Frederick Douglass’s arrival in Ireland

Frederick Douglass was 27 years old when he arrived in Dublin on the 31st of August 1845. He had crossed the Atlantic from Boston to Liverpool and then traveled on to Ireland.

Douglass was born into slavery in Maryland in 1818 and twenty years later fled north and settled in Massachusetts where he could live, albeit precariously, as a freeman. He went on to become a lecturer for the American Anti-Slavery Society and in 1845 published his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Given the risk that he might be captured by slave hunters and returned to slavery, he was advised to take refuge across the Atlantic where he could promote his book. He travelled to Ireland in connection with its publication and remained there for the rest of 1845. Douglass became a popular figure in Ireland and his time there left a lasting impact on him.

Ireland was fertile ground for Douglass’s abolitionist message. Other freed slaves had been to Ireland before him, notably Olaudah Equiano, author of The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, who visited in 1791. They had been well-received in Ireland where anti-slavery sentiment was and continued to be impressively strong. I saw evidence of this when I visited Frederick Douglass’s home in Anacostia near Washington last year and was intrigued to be shown an elaborate address of welcome presented to him by Cork City’s anti-slavery societies This means that a city of perhaps 100,000 inhabitants had multiple abolitionist groups in the 1840s. Douglass spent almost three weeks in Cork in October 1845.

Douglass’s principal hosts in Ireland were members of the Quaker community, including his Dublin publisher, Richard Webb, whose son, Alfred, went on to become a prominent Home Rule MP. During his visit, Douglass delivered lectures on slavery and temperance in Dublin, Cork, Waterford, Wexford, Youghal, Limerick, Celbridge, Bangor, Lisburn and Belfast. His staunch advocacy of temperance caused him to strike up a friendship with Ireland’s chief temperance crusader, Father Theobald Mathew (1790-1856) although they later parted ways when Fr Mathew on a visit to America refused to condemn slavery. Douglass believed that many of Ireland’s ills were due to the pernicious impact of alcohol on its people.

Frederick Douglass cut quite a dash during his Irish visit. Newspaper reports described him as “a fine-looking man, possessed of a full flow of natural eloquence” and as someone with “a manly dignity of manner”. His “robust frame” and “very pleasing expression of countenance” were also commented upon.

Douglass’s sojourn in Ireland was not without its controversy. One of the key themes of his Irish speeches concerned “the anti-Christian nature of slavery.” His sharp critique of America’s Protestant Churches on account of their support for slavery, although it probably went down well with Catholic members of his audience (not that America’s Catholic Church was without blemish when it came to the question of slavery), met with resistance from some Irish Protestants as did his attack on Scotland’s Free Presbyterian Church for taking money from American slaveholders.

One of the undoubted highlights of Douglass’s visit was his encounter with Ireland’s Liberator, Daniel O’Connell (1775-1847). I first became aware of the link between O’Connell and Douglass when I was posted in Berlin and was invited to the City of Cottbus to celebrate the life of a local luminary, Prince Hermann von Pückler-Muskau (1785-1871), who visited O’Connell at his home in Co. Kerry in 1828. Examining Pückler-Muskau’s visit to Ireland brought home to me the extent of O’Connell’s stellar reputation across Europe. When I spoke about this at the O’Connell Summer School at the Liberator’s home at Derrynane in 2013, I did so in the company of Nettie Washington Douglass, great-granddaughter of Frederick. In her speech, she highlighted O’Connell’s reputation in America as a champion of abolition, and his connection with her famous ancestor.

O’Connell had been an opponent of slavery since the 1820s and had never wavered in this position, even when it might have been politic to do so. He did not hold back in his verbal assault on slavery which he saw as “a foul stain” on America’s character. He caused a stir in the 1830s by publicly accusing the American Ambassador in London of being “a slave breeder” after which the Ambassador threatened to challenge O’Connell to a duel. Even when it came to America’s Founding Fathers, O’Connell did not flinch, accusing them of lacking the “moral courage” to abolish slavery. This uncompromising stance put him at odds with many Irish Americans and in 1843 he decided to refuse financial support from those in America who supported slavery. His abolitionist fervour was one of the issues that came between him and the members of Young Ireland who thought it unwise to alienate America and Irish Americans on the issue of slavery.

It is hardly surprising therefore that Douglass should have been keen to seek out O’Connell during his time in Ireland. In speeches he delivered after his arrival in Ireland, he was shrewd enough to heap praise on O’Connell which went down very well with his audiences in Dublin. Then, at a Repeal meeting in Dublin on September 29th, O’Connell and Douglass crossed paths. Douglass revealed that he had known of O’Connell when he was enslaved and had heard him cursed by his slave-owning masters. Douglass reported to the American anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator, on the speech O’Connell delivered that day. It was stirring stuff. “I am an advocate of civil and religious liberty all over the globe, and wherever tyranny exists, I am the foe of the tyrant: wherever oppression shows itself, I am the foe of the oppressor: wherever slavery rears its head, I am the enemy of the system ..”. O’Connell went on to say: “My sympathy with distress is not confined within the narrow bounds of my own green island. No – it extends to every corner of the earth. My heart walks abroad, and wherever the miserable are to be succored, or the slave to be set free, there my spirit is at home, and I delight to dwell.” Understandably, Douglass was mightily impressed by O’Connell: “His eloquence came down upon the vast assembly like a summer thunder-shower upon a dusty road.”

When it came to Douglass’s turn to speak, he said that: “The poor trampled slave of Carolina had heard the name of the Liberator with joy and hope, and he himself had heard the wish that some black O’Connell would rise up amongst his countrymen, and cry ‘Agitate, agitate, agitate’. Although their encounter was brief, the ageing, ailing O’Connell left a profound mark on the younger man who often referred to him down the decades that followed.

Douglass was gratified by the manner in which he was received in Ireland. He was struck by the “total absence of all manifestations of prejudice against me, on account of my color. .. I find myself not treated as a color, but as a man.” He contrasted this with his lot in America: “The land of my birth welcomes me to her shores only as a slave, and spurns with contempt the idea of treating me differently.”

Frederick Douglass came to Ireland at just the right time. 1845 was a year when Daniel O’Connell, although physically ailing, was still at the height of his political renown. By that time, he had established himself as one of Europe’s premier opponents of slavery. O’Connell’s views on the subject no doubt swayed many Irish people to share his views hence the enthusiastic welcome accorded to Douglass. Had he arrived a year or two later, he would have found O’Connell’s influence in sharp decline. Moreover, the increasingly severe impact of the Great Famine in 1846 and 1847 would have made it much harder for him to attract the kind of attention and support that came his way in 1845.

Looking back, I believe that we can draw satisfaction from the fact that Douglass was so well received in Ireland and that his anti-slavery message resonated strongly with the Irish public. Burdened by their own sense of grievance at the social and economic conditions that were the lot of the majority of the Irish people in 1845, there was an evident feeling of affinity with those who suffered under the yoke of slavery. Nonetheless, as Douglass made clear, the situation of the Irish, while they suffered from depravation and discrimination, was a far cry from what he had endured during his life as a slave in Maryland. The Irish had the right to leave and seek new lives for themselves in the USA and elsewhere. For his part, Douglass was able to find a new life for himself during the months he spent in Ireland. He built upon that new life with immense distinction upon his return to the USA.

Today, we celebrate Ireland’s connection with Frederick Douglass on the 175th anniversary of the months he spent on our shores. We do so because of our recognition of Douglass’s historic importance and because this story resonates in an Ireland that is now more ethnically-diverse and multi-racial than it has ever been before. The Douglass story is also important as we reach out to African Americans who are part of a multifarious Irish diaspora whose breadth and heterogeneity we now recognize and celebrate.

Daniel Mulhall is Ireland’s Ambassador in Washington DC.

« Previous Item | Next Item »